Boiling Down Dietary Cancer Risks

By Paul Brockwell Jr., MCV Foundation

Food is more than just fuel for the body.

It’s often about the experience, the panoply of flavors and aromas — from the simple browning of a crispy slice of toast to the sweetness of caramelized onions. But behind the most delicious foods and flavors is a source of cellular inflammation that has led to growing concern among top cancer prevention researchers.

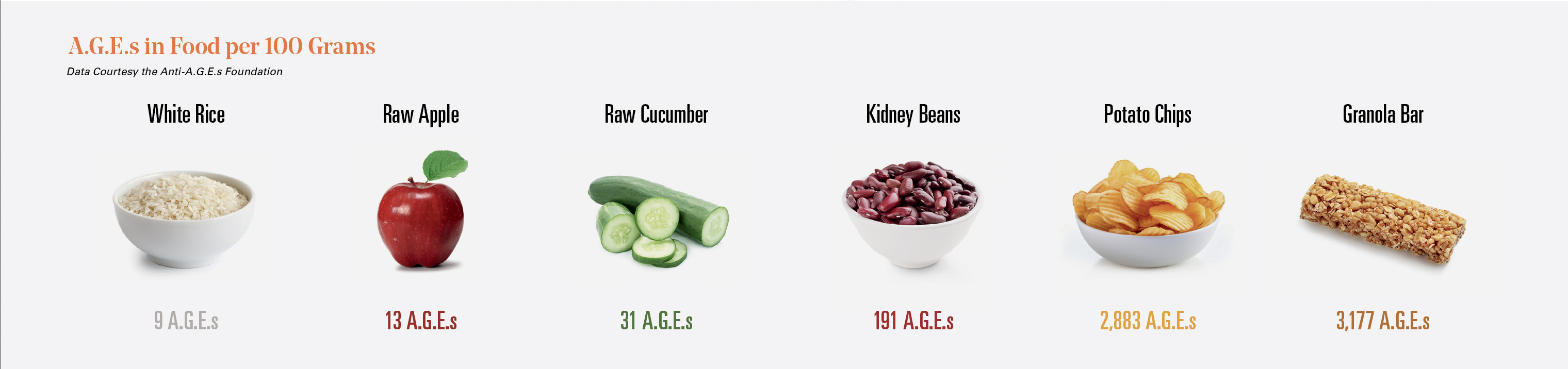

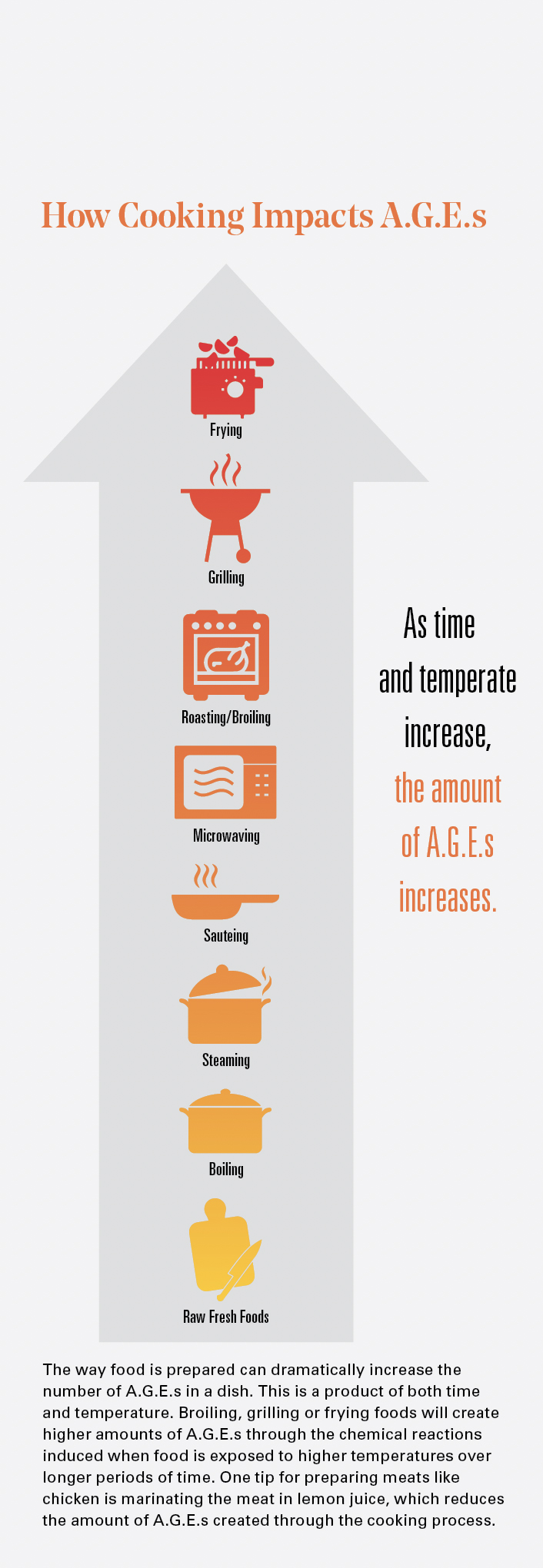

Nearly every food naturally contains what’s known as advanced glycation end products (A.G.E.s). The amount of these metabolites can be supercharged depending on how food is processed and prepared. A raw apple, for example, contains 13 A.G.E.s. Cooking leads to the formation of new A.G.E.s, especially when food is cooked at higher temperatures for a long time. The amounts can increase depending on the method.

In addition to being consumed through food, A.G.E.s are formed within the body as sugar combines with fat, protein and even genetic material in a complex series of reactions known as glycation. Human bodies are only capable of eliminating a fraction of the A.G.E.s they consume. Over time, they accumulate in tissues and organs, causing increased oxidative stress and inflammation that research suggests contributes to chronic diseases throughout the body.

“Advanced glycation end-products” is hardly a household term … yet. But a pair of researchers at VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center are working to create greater awareness of the role they play in driving the body’s inflammatory responses, more rapidly aging the body and increasing cancer risk.

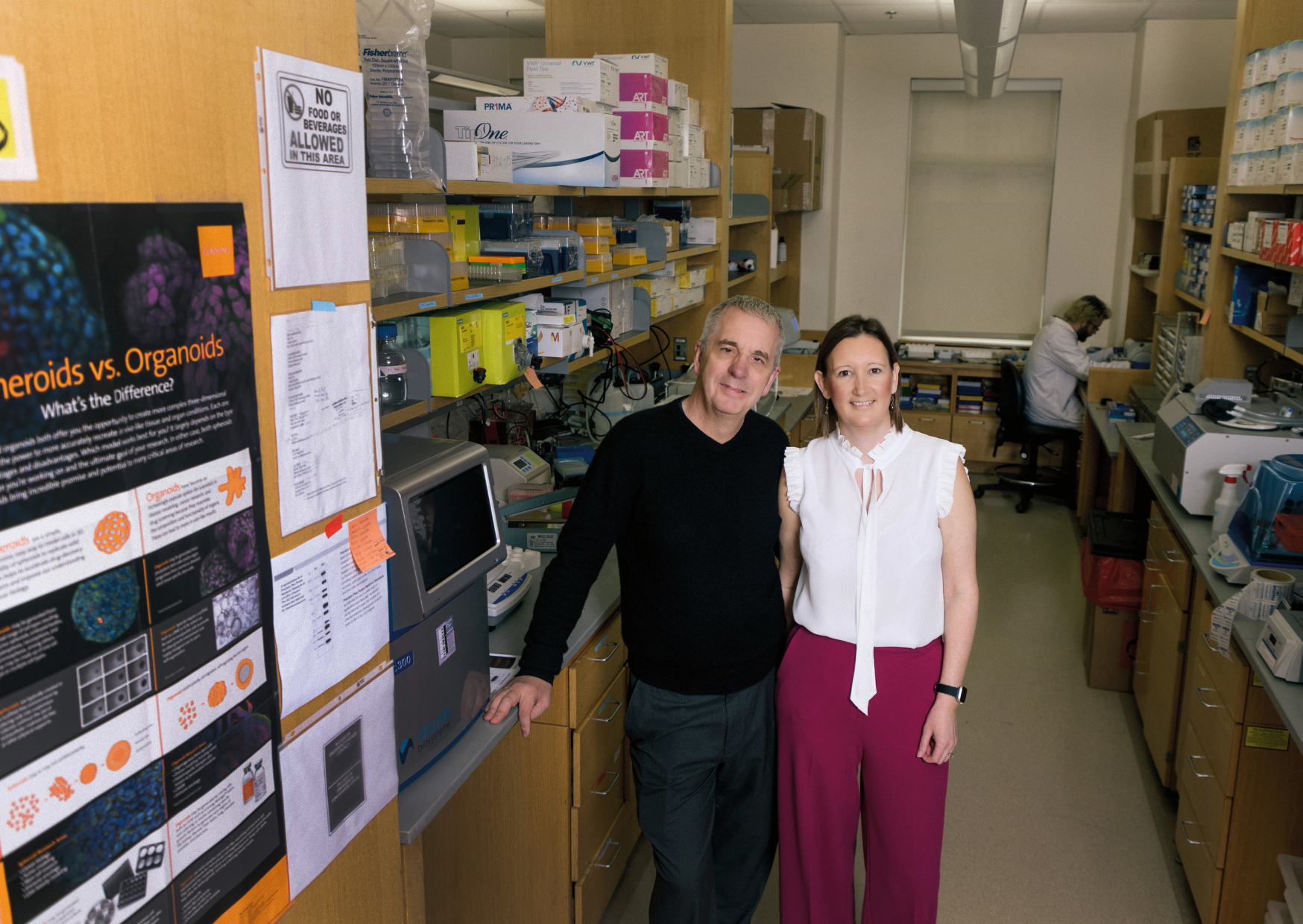

Victoria Findlay, Ph.D., co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Program at Massey, is the primary co-investigator along with her husband, David Turner, Ph.D., on a project funded by the National Cancer Institute that focuses on A.G.E.s and their negative impact on cancer risk. Both are associate professors in the Department of Surgery at the VCU School of Medicine.

The difficulty is that most people are unaware of the existence of A.G.E.s, let alone the damage that they cause.

Victoria Findlay, Ph.D., co-leader, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center and associate professor, Department of Surgery, VCU School of Medicine

Most people have not heard about A.G.E.s, but Drs. Findlay and Turner have been researching them for around a decade and building a better understanding of their connections with dietary lifestyle choices and increased cancer risks. What they’ve discovered has been motivating beyond the lab.

The pair were part of a four-person team that co-founded the Anti-A.G.E.s Foundation to promote understanding of A.G.E.s and to educate the general public about A.G.E.s and the keys to lowering consumption rates in one’s diet. Both Dr. Findlay and Dr. Turner are currently rowing against the tide. Today, people consume A.G.E.s at an all-time high, thanks to the ubiquity of ultraprocessed, low-cost foods. An innocent-looking granola bar nets over 2,000 A.G.E.s. Three bacon slices contain a sizzling and crispy 91,577 A.G.E.s.

“The difficulty is that most people are unaware of the existence of A.G.E.s, let alone the damage that they cause,” Dr. Findlay said. “Currently, there are no databases or resources detailing this information. This is where we hope the Anti-A.G.E.s Foundation can help. Our mission is to make the world more aware of A.G.E.s by creating dynamic educational resources that provide information on the links between modern nutritional habits, chronic diseases and A.G.E.s.”

RAGING A.G.E.s

A diet high in A.G.E.s will, over time, slowly wreak havoc in the human body. A.G.E.s are a metabolic byproduct of complex interactions between sugars and fat, protein and genetic material. The body cannot fully process or eliminate A.G.E.s, and research strongly suggests that A.G.E. accumulation is connected with chronic inflammation.

A diet high in A.G.E.s will, over time, slowly wreak havoc in the human body. A.G.E.s are a metabolic byproduct of complex interactions between sugars and fat, protein and genetic material. The body cannot fully process or eliminate A.G.E.s, and research strongly suggests that A.G.E. accumulation is connected with chronic inflammation.

“What’s different about A.G.E.s is it’s a spontaneous reaction. It’s not a controlled reaction,” Dr. Turner explained. “It’s a bit like when two magnets come together, when a protein and a sugar come together, they’re pulled together and form this A.G.E.”

After A.G.E.s form, they can interact with receptors on the outside of cells, which are involved in controlling the body’s immune response. When a person gets a cut or scrape on their skin, one of these receptors, called the receptor for A.G.E., or RAGE, helps to recruit immune cells to come fight any infection, creating the redness and telltale signs around a cut or scrape. If humans have too many A.G.E.s in their bodies, it can cause RAGE to recruit too many immune cells and can lead to inflammation in tissues. Ironically, the presence of inflammation can lead to the formation of more A.G.E.s and further RAGE activation, leading to persistent chronic inflammation.

A.G.E.s are really understudied. And we’re driving that forward especially when it comes to food and cancer.

David Turner, Ph.D., associate director, Community Outreach and Engagement, VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center and associate professor, Department of Surgery, VCU School of Medicine

“It’s a complicated feed-forward loop,” Dr. Turner said. “And we know that virtually all chronic diseases are driven by inflammation. It’s central in cancer, diabetes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Persistently causing chronic inflammation is where A.G.E.s really have an influence on most chronic diseases. Through their intrinsic ability to perpetuate immune-mediated inflammatory stress, A.G.E.s found in the diet represent an early life exposure that may influence the onset and/or severity of multiple chronic conditions when we grow older.”

A.G.E.s also adhere to tissues and organs during these complex reactions in ways that are irreversible, according to Dr. Turner. “For example, over time when A.G.E.s accumulate and bind to the protein collagen in the skin, it can contribute to the formation of wrinkles in the skin as we grow older,” Dr. Turner said. “If you can imagine the same thing happening to every organ in your body, A.G.E.s can make your organs grow older quicker. So you might be 35 years old, but if you’ve been exposed to a lot of A.G.E.s over your lifetime, the deterioration of your organs may reflect a 45-year-old.”

A.G.E. INSIGHTS FUEL RECENT RESEARCH

A.G.E.s have been known for more than a century since French chemist Louis Maillard began studying the interactions between amino acids and sugars in 1912. In fact, the chemical reaction called the Maillard reaction, which can be seen when a slice of bread slowly transforms into a perfect golden-brown piece of toast, is named after him. But it was only in the last two decades that research on A.G.E.s and cancer really began.

“A scientist’s journey is never one straight line,” said Dr. Findlay. “You let the science take you wherever it guides you.”

For her husband, Dr. Turner, the science started leading him toward A.G.E.s while at the Medical University of South Carolina. A research partnership with South Carolina State University, a historically Black university, led him to some really astonishing insights about A.G.E.s that raised health equity concerns for communities with high cancer rates and where access to food is often limited to cheaper, ultraprocessed foods high in A.G.E.s.

“Fifteen years ago I’d never heard of A.G.E.s, so we had to do a lot of research on this,” Dr. Turner said. “Once we found out what they were, we wondered, ‘Why isn’t everybody looking at these?’ They just seem so important. Based on that alone, we both sort of changed our research direction.”

At that time, there was one paper that looked at the role of these A.G.E.s in cancer development, Dr. Turner said. They seemed such an important area of inquiry for the duo since they’re involved in all the foods people eat and the way they live their daily lives, and therefore can be part of understanding what lifestyle choices actually lead to cancer.

What they found set off some alarm bells. Data from several studies the pair have conducted have indicated that high-A.G.E. diets may cause prostate and breast tumors to grow faster. These studies provide evidence that consuming a diet high in A.G.E.s may create an environment around existing tumors that helps them to grow by causing RAGE activation. “We expected to see effects, but we didn’t quite expect the extent of what we’re seeing in our experiments,” Dr. Findlay said. “Our study measured a three- to fourfold increase in tumor growth due to A.G.E.s in our experimental models, which is a lot.”

“A.G.E.s are really understudied,” Dr. Turner said. “And we’re driving that forward especially when it comes to food and cancer. All of our data has indicated that A.G.E.s in the diet, especially the preformed A.G.E.s in food, seem to be making the cancers grow quicker and be more aggressive.”

Further studies are required to support the experiments that Drs. Findlay and Turner have performed in the laboratory, and while this research continues, the pair have also explored potential interventions.

Dr. Findlay has examined how time-restricted eating can blunt the impact of high-A.G.E. diets by limiting eating from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., for example. The results were compelling enough for her to adopt the practice into her own lifestyle. Collaborative studies between Drs. Findlay and Turner and other labs also support the theory that women who are consuming the most A.G.E.s may be at higher risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer.

“We never expected to see the magnitude of changes that we saw when we did dietary studies,” Dr. Findlay said. “We’re not genetically manipulating anything — it’s literally just a diet. We truly believe that A.G.E.s within the food — and not just individual fat or sugar or protein — is really driving a lot of the chronic diseases that we’re observing.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

Drs. Findlay and Turner are enthusiastic about continuing this research and its potential for positive impact. They hope that by creating a better understanding of the role A.G.E.s play in chronic inflammation and diseases, they can help inform long overdue policy and regulatory discussions on food. They have enjoyed engaging with the community, especially in primary schools, because they believe that by educating children early, they can have a ripple effect with their parents at home around the dinner table.

“We’re about to put a list of 560 foods and their A.G.E. counts in various cooked formats on the website for the Anti-A.G.E.s Foundation,” Dr. Turner said. The study was done by Jaime Uribarri, M.D., in New York. “I think that it would really help to get people to understand how many A.G.E.s they are consuming. Right now, few people know what A.G.E.s are, but if we educate people, they are then free to make their own decisions on A.G.E.s. They could totally ignore what we tell them, but if people aren’t told, they can’t make an informed decision about the foods that they’re eating.”

Initial studies in healthy individuals indicate that a consumption of between 15,000 to 20,000 A.G.E.s per day may be a healthy limit. However, Dr. Findlay is quick to share that further research is needed to definitively assign a recommended daily ceiling on the amount of A.G.E. consumption per day.

“The body can detoxify some, but not all A.G.E.s, and there is not yet enough research to show how much is truly too much,” Dr. Findlay said. “There is no dietary requirement for A.G.E.s that we are aware of, thus ‘less’ is definitely better.

“We hope this research helps allow people to understand how their lifestyle choices can help reduce the risk of cancer and chronic diseases later in life,” she continued. “People don’t understand the power they have over their own bodies until it’s often too late.”

If you are interested in supporting research at VCU Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, please contact Caitlin Doelp, Massey’s executive director of development, at 609-432-6247 or doelpc@vcu.edu.

Discover More

Read more features like this in the summer issue of NEXT magazine.