The Gene Edit

This story was first published in our Summer 2024 issue of next magazine. Please access the full issue here.

By Holly Prestidge, MCV Foundation

Photos by Daniel Sangjib Min, MCV Foundation

Walter Davis recalls few stretches throughout his 30 years on this earth when he did not measure the quality of his life on a pain scale.

Good days were 2s, maybe a 3. Life seemed almost normal. A heating pad’s warmth soothed minor aches and pains.

An 8 or a 9, on the other hand, put him back in the hospital, in severe pain all over his body, his spirit falling deeper into a familiar darkness that he sometimes felt would swallow him.

Davis, who lives in Colonial Heights, was born with sickle cell disease, a genetic red blood cell disease that affects about 100,000 people annually in the U.S., predominantly African Americans.

Symptoms include anemia, debilitating pain, organ failure, strokes — the list goes on. Every patient experiences this disease differently. For decades, treatments have been only reactive, usually when the patient is already in a lot of pain. Preventive therapies that could shut down production of sickle cells at the start — considered the “holy grail” for sickle cell disease — were elusive.

But a successful clinical trial at VCU Health involving gene therapy has potentially broken through that barrier.

The Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU and the VCU Medical Center are now the only qualified treatment centers in Virginia offering a newly approved sickle cell therapy that uses an individual’s own stem cells with modified hemoglobin genes to produce healthy red blood cells.

The groundbreaking therapy, approved in late 2023 for patients 12 and older, was conducted as part of a clinical trial for which VCU Health was selected as a test site several years ago. Those involved say they were chosen thanks to the sophisticated, multifaceted collaboration that exists between ChoR’s pediatric comprehensive sickle cell center and the adult program at VCU Medical Center that addresses every age and phase of sickle cell, from newborns and children through the transition to adulthood.

The therapy works like this: Patients are given medicine that effectively knocks out their bone marrow, which triggers the bone marrow’s defense mechanisms to produce more stem cells as quickly as it can. Those extra stem cells are collected and sent to a partner company that specializes in gene modification. While there, the patients’ genes — those that create hemoglobin — are modified via the introduction of a virus.

There’s still a lot of issues with health disparities around sickle cell because it’s not a disease that communities openly talk about.

India Sisler, M.D., interim division chief and clinic director, Division of Hematology and Oncology and medical director, pediatric sickle cell center, Children's Hospital of Richmond

The gene modification allows the cells to produce a new kind of hemoglobin that allows the cells to function as a healthy red blood cells. Those cells are then returned to Richmond, where they are given back to the patient through an autologous stem cell transplant.

Groundbreaking, life-changing — the descriptors do not nearly come close to the feelings that physicians, researchers and countless others are experiencing as they now watch and study the therapy’s effects.

In short, all eyes are on Davis.

At 28 years old, he was a willing, if not indifferent, participant. From his perspective, he recalled, it was just another clinical trial. Nothing had worked to that point, yet he continued to experience pain in new parts of his body. He felt defeated and he was tired.

Tired of pain, tired of hospitals, tired of living.

What was one more trial, he remembers thinking. He had nothing left to lose.

The Turning Point

Red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body. Sickle cell disease occurs when a mutation in the DNA that produces hemoglobin — one of the building blocks of red blood cells — causes those cells to be sickle-shaped, like a half-moon or a crescent.

The sticky, abnormally shaped cells don’t carry oxygen efficiently and form blockages within the body. Over time, that lack of oxygen affects everything from the brain down to the toes.

Sickle cell can affect anyone, though it is most prevalent in African Americans. One in 13 African American babies is born with the sickle cell trait and 1 in 365 has the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Individuals can be carriers of the sickle cell trait and never experience symptoms. But if two carriers have a baby, the chance of that baby having sickle cell disease rises to 1 in 4. Symptoms from the disease typically start early, sometimes in babies only a few months old. As the children grow, so does their pain.

As recently as the early 1970s, the lifespan for individuals with sickle cell disease was a painful 14 years. Those who made it to adulthood faced grim realities: eventual organ failure, strokes, infections and blindness. As a result, sickle cell research took an unusual path.

“It’s one of the only places in medicine where breakthroughs happen in pediatrics and then trickle into adult medicine,” said India Sisler, M.D., interim division chief and clinic director of the Division of Hematology and Oncology and medical director of the pediatric sickle cell center at CHoR. “Typically, you’re going to make sure something is safe in adults before testing on a child, but because historically there hasn’t been adult sickle cell care, a lot of what we know about sickle cell started in pediatrics.”

In addition, historically underrepresented populations with little or no access to medical care are those with the highest instances of sickle cell, and that underscores the importance of addressing sickle cell as a disparity disease, she said.

“There’s still a lot of issues with health disparities around sickle cell because it’s not a disease that communities openly talk about,” Dr. Sisler said. “Even among health providers today there are discrepancies with regard to care and treatment.”

Wally Smith, M.D., director of the VCU Adult Sickle Cell Program and the inaugural holder of the Florence Neal Cooper Smith Professorship in Sickle Cell Disease Research, echoed those remarks.

He explained that sickle cell was discovered in parts of the world where malaria was present. It was a survival advantage, as those who carried the trait were believed to be less susceptible to severe forms of malaria.

In the U.S., sickle cell care and awareness began changing in 1972 with the passing of legislation called the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act. The law put key measures into place, including required screenings for newborn babies.

That same year, the Virginia Sickle Cell Anemia Awareness Program was established on the MCV Campus. Efforts were led by Richmond’s own Florence Neal Cooper Smith, affectionately known as the “mother of sickle cell” in Virginia for her advocacy.

“We did a lot in the U.S. to make it so children could live,” Dr. Smith said about the years following the legislation. Screenings offered a clearer picture of just how many people were affected. Infants and children were given penicillin. By the 1980s, hydroxyurea, a drug still used today, could reduce the number of pain episodes in sickle cell patients. By 2000, vaccines existed to nullify infections from other diseases in people who were at greater risk due to sickle cell.

In the last decade, bone marrow transplants — where bone marrow is knocked out by chemotherapy and replaced by donated stem cells — have increasingly been successful in treating patients with sickle cell disease.

Today, 95% of individuals living with sickle cell disease survive into adulthood. Those positive outcomes are driven by better treatment of the symptoms, but gene therapy offers promising progress toward a longterm cure.

The new therapy in trials at VCU Health still doesn’t completely eliminate the underlying genetic causes, but it is a therapy on the cusp of revolutionizing sickle cell care.

“It’s space-age,” Dr. Smith boomed. “It is a landmark — a turning point for man.”

The therapy has also been approved for patients with beta thalassemia, a red blood cell disease in which the body does not make enough red blood cells. In those cases, the therapy has been approved for ages 4 and up.

VCU Health is a leader in sickle cell research and care, Dr. Sisler said, because of the collaborative nature of robust teams that work across the pediatric and adult health spectrums. That’s transplant specialists, oncologists and pathologists, as well as nurses, social workers and more.

“We take a lifespan approach to care,” she said. “We are already recognized for our expertise in sickle cell care and research, and this is just the natural progression that leads to being on the forefront of transformational therapies for patients.”

Dr. Smith went on to say that CHoR and the VCU Medical Center expect to be named as qualified treatment sites for a second and different gene therapy, possibly later this year.

For the current therapy, there are approximately 30 qualified trial sites nationally, but as Virginia’s only site, Dr. Smith said there are already patient referrals coming in from neighboring states.

Beth Krieger, M.D., a pediatric hematology and oncology specialist at CHoR, said the therapy doesn’t yet work for everyone with sickle cell. If comorbidities exist such as a previous stroke, or their symptoms aren’t severe enough and they haven’t had enough qualifying pain events, patients are not eligible for the therapy. Qualifying pain events are those that bring patients to the hospital for pain treatment, including emergency room visits, or more serious cases, like when they’re having trouble breathing or need blood transfusions.

There are many patients with sickle cell but not many treatment centers yet — or even enough of the therapies from the drug companies to tackle the current need.

“Figuring out how to get the greatest number of patients who qualify and are interested in the therapy is what we’re concentrating on right now,” Dr. Krieger said, and not just from Virginia or neighboring states. “We’re thinking globally because the vast majority of patients with red blood cell diseases don’t live here in the United States.”

“My hope,” she added, “is that every child in the future whose parents are interested in a curative therapy will be able to get it.”

‘He showed us the way’

Thokozeni Lipato, M.D., an assistant professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the VCU School of Medicine, first started working with Davis as a young adult about 10 years ago when Davis transitioned from pediatric care at CHoR to VCU Health’s adult program.

While the therapy is administered by the pediatric team, the adult program encompasses everything that follows, from medical inpatient and outpatient treatment to support services for mental and social health. Today, the adult center serves about 1,200 individuals.

What struck Dr. Lipato was how diligently Davis followed his medical orders when he was a child. In fact, Davis was so dedicated that his red blood cell count at one point was better than some patients who had received blood transfusions.

“There was this light in him,” Dr. Lipato said. “He was fairly symptomatic, but he still had all of his hopes and dreams. He wanted to have a normal life and he truly believed that was still in his future.”

That light, however, went out.

As Davis entered his early 20s, his pain became more frequent and more severe. He was in and out of the hospital. He couldn’t hold a job. Davis loved working out and being fit, but he couldn’t because he hurt all the time.

“I saw him slipping,” Dr. Lipato said.

Davis had been on narcotics for pain since he was 11. By the time he reached adulthood, he was physically dependent on the drugs, and that dependency was another medical condition.

“When the medication runs out, when the stress goes up, that physical dependency plays a role in how the pain manifests,” Dr. Lipato said, adding while Davis’s dependency was deep, it never reached addiction levels.

“But this cycle began, and his mental health just took a nosedive,” Dr. Lipato said. “I saw that light go out and what you’re left with is this young man in the hospital all the time, on a lot of pain medication.”

Adding to the downward spiral was faith lost. No treatment had worked. For all his compliance, his willingness, his trust in his doctors, nothing was making him better.

“To his credit, he did everything we asked him to do and still, he fell into this hole,” Dr. Lipato said.

But when the gene therapy clinical trial became available, Dr. Lipato said he immediately thought of Davis, who fit the criteria: He was young enough and symptomatic enough. But more importantly, Davis had always trusted his doctors and followed their orders.

Dr. Lipato asked. After weeks of consideration, Davis agreed.

The trial took about a year. Davis’s stem cells were collected and shipped off to the partner company. After several months, they came back, and Davis was back in the hospital last spring for the stem cell transplant. Little by little, his red blood cell counts improved.

By last fall, his blood counts looked like a patient with sickle cell trait but not the disease.

He will continue to be monitored at VCU Health.

“He always thanks me, but I thank him,” Dr. Lipato said. “We could only do this because he basically stood up and said, ‘I’ll do it — I’ll be the first one.’ What this has afforded VCU, and me personally, is really being at the forefront of this revolutionary medical treatment, and we learned how to do it because he showed us the way.”

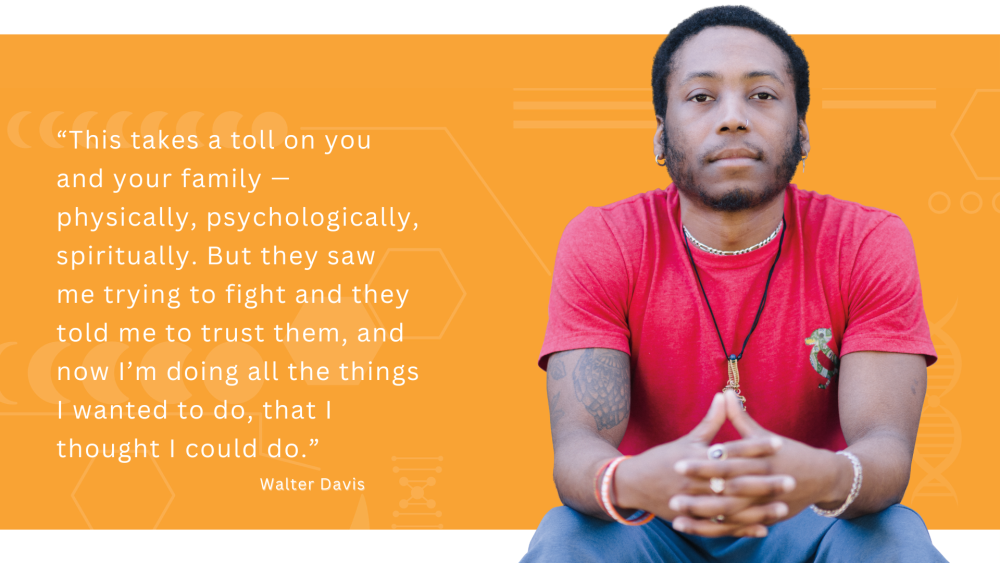

Davis grins as he talks about his life now. His body feels good. He can work out and he’s taken up boxing for exercise. He’s thankful for medical teams in his corner who saw something in him when he was ready to give up.

“This takes a toll on you and your family — physically, psychologically, spiritually,” he said. “But they saw me trying to fight and they told me to trust them, and now I’m doing all the things I wanted to do, that I thought I could do.”

Davis isn’t ready to say he’s cured.

“But it is the closest thing to a cure,” he said. “I had to think of the bigger picture because this therapy, it could not only help me but also other people, too, and I’m happy and proud to be part of that.”

If you would like to learn more about how you can support sickle cell research at VCU Health, or make a contribution to the Florence Neal Cooper Smith Professorship, please contact Brian Thomas, the MCV Foundation’s executive vice president and chief development officer, at 804-828-0067 or brian.thomas@vcuhealth.org.

Make a Difference

Support sickle cell research at VCU Health.