Ken Kendler Circles the Globe in Pursuit of Psychiatry Breakthroughs

This profile is part of a larger story, "VCU Health: A Global Leader in Mental Health".

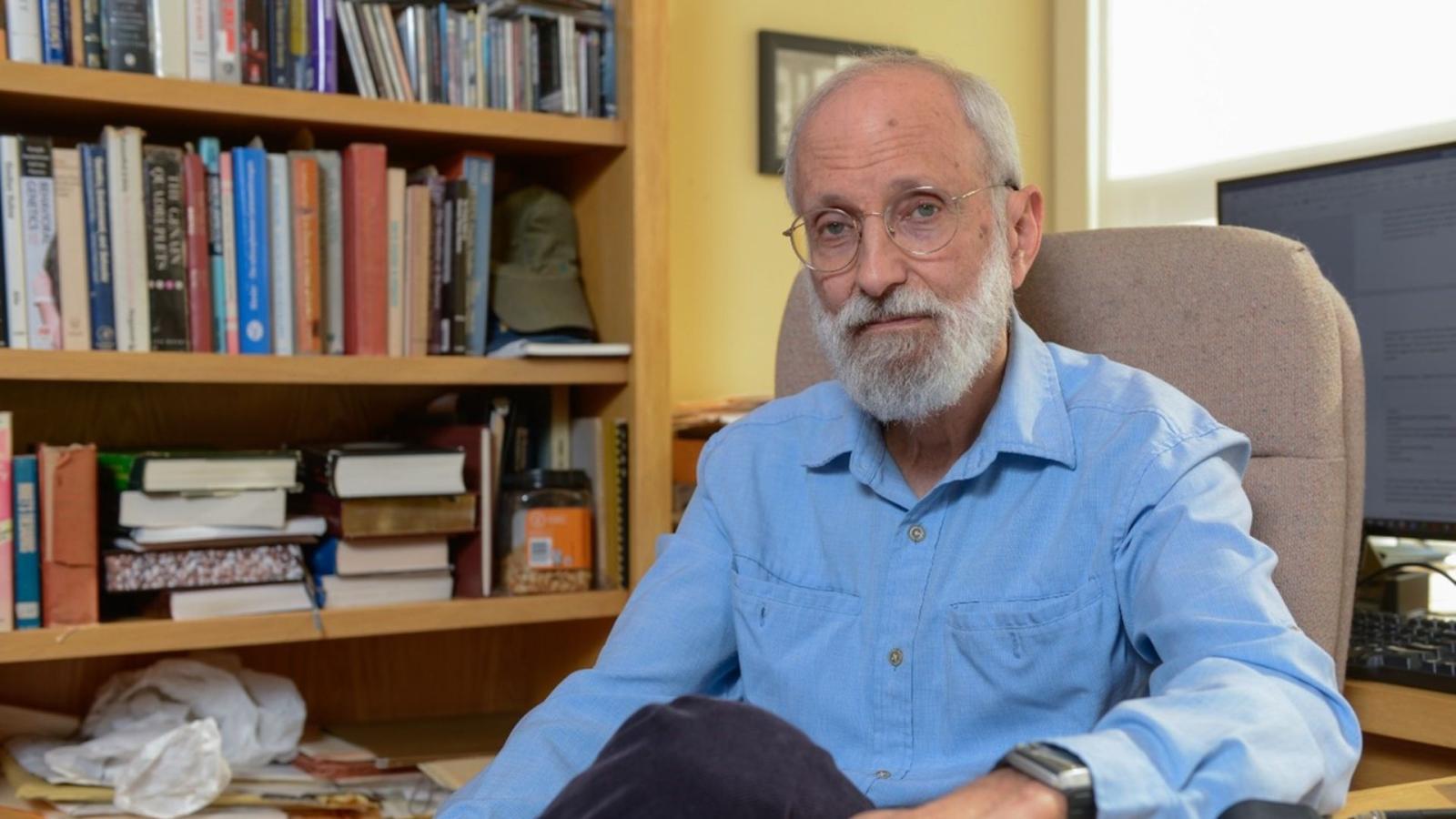

Most conversations about Kenneth S. Kendler, M.D., include some reference to his status as one of the most cited psychiatry experts in the world.

His research examines the ways in which molecular genetics coupled with environmental factors lead to psychiatric disorders like alcoholism, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, drug abuse and other challenges. And those who talk about the sheer volume of citations credited to his research are right — Dr. Kendler has routinely ranked as a top-five most cited psychiatry researcher over the past four decades.

In 2011, he became only the second American psychiatrist to receive the World Psychiatric Association’s Jean Delay Prize, an award known as the Nobel Prize of psychiatry.

Always good-natured, Dr. Kendler shakes off his many accolades by noting that scientists do not work in isolation. Since his 1983 arrival on the MCV Campus, he said he’s been blessed to work in an environment that supports his passion to tap into potentially unchartered nuances of the human psyche.

In his role as director of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics at VCU and the Rachel Brown Banks Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry in the VCU School of Medicine, Dr. Kendler is at work on three large-scale international research projects that are redefining how psychiatry is understood.

There is a need both for research and social equity purposes to be able to develop datasets in non-Western populations.

Predicting Major Depression

Dr. Kendler serves as co-principal investigator on the first project, the largest-ever population study examining the genetic variations that affect individuals’ risks for depression. The five-year project, funded in 2021 by a nearly $9 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, aims to study 20,000 women in South Korea.

The study’s goal is to understand the major causes of depression and potentially unlock biological mechanisms to treat it in the future by accurately predicting — through molecular genetic testing — someone’s vulnerability to major depression. Thus far, 2,500 cases have been identified and 3,000 controls have been ascertained. The research team includes representatives from 40 hospitals throughout South Korea.

“We have an excellent set of collaborators,” Dr. Kendler said. “What makes this study relatively unique is the sample size, the restriction of ethnicity and gender, only studying recurrent major depression, and then using this deeply phenotype approach that allows us to probe more intensely than other studies for subtypes that might be genetically linked.

“The background of that is significant in that, in psychiatric disorders, the boundaries are not precisely known,” he continued. “It is critical that we allow the genetic results and the diagnostic assessments to interrelate to one another to find whether there are subgroups of depression.”

Cross-Cultural Psychiatry

Dr. Kendler also is involved in the Asian Bipolar Genetics Network project, which considers cross-cultural psychiatry while addressing the lack of social equity in global medical research.

“If you looked five years ago at all of the work being done in molecular genetics of general diseases, especially psychiatric diseases, 98% of that would have been in white Europeans,” he said. “There is a need both for research and social equity purposes to be able to develop datasets in non-Western populations.”

As a key collaborator overseeing data collection, Dr. Kendler is working in Taiwan, South Korea, India, Vietnam and Singapore.

“The problems of phenotype assessment are really quite striking,” he said, particularly in how doctors and scientists assess bipolar illness. In patients experiencing mania, he said, more than half will develop grandiose delusions.

“The classic patient example that you’d see in an emergency room is a young man coming in saying he’s Jesus Christ,” Dr. Kendler said. “He’s talking quickly, animated.”

But, he added, “what is that going to be like in India with Indian mythology — how many patients will experience grandiose ideations, if they come from various Buddhist cultural backgrounds or Hindu backgrounds?

“With these two projects, the largest payoff would be an increase understanding of the genetic-biological causes of these disorders,” he said, “and the opportunity to provide new drug targets that could lead to more effective medication development.”

We’re a high-performing group and this work would not be possible without a key number of collaborators. They’re all critical to our success.

Medicine of the Body vs. Medicine of the Mind

Finally, Dr. Kendler is expanding a decades-long study on depression and anxiety to include boundary disorders — those disorders that exist at the boundary between classic somatic medicine and psychiatry. The study will focus on three conditions: fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome.

“This is a study where we’re not only going to try to dive deeply into the etiology of more traditional anxiety and depression,” he said, “but try to understand how those relate to these chronic and quite disabling boundary disorders.”

A Global Influence

Dr. Kendler’s influence spans the globe. He’s published more than 1,200 articles. His research and data collection has taken him to Ireland, England, China, Norway, Finland and Sweden, as well as South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, India and the Netherlands.

Dr. Kendler’s influence spans the globe. He’s published more than 1,200 articles. His research and data collection has taken him to Ireland, England, China, Norway, Finland and Sweden, as well as South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, India and the Netherlands.

He’s overseen the creation of several recent editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the handbook widely used by U.S. physicians and psychiatrists to identify mental illness, serving as former chair of the Scientific Review Committee and now as vice chair of the American Psychiatric Association DSM Steering Committee.

He is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and editor of Psychological Medicine.

Dr. Kendler has also impacted generations to come by serving as mentor to many, from junior faculty to post-doctorate and graduate students at VIPBG to international junior colleagues. Through it all, he expressed gratitude for the support he’s received at VCU over the decades, as well as appreciation for private endowments that allow him and his peers to advance their research

“I’ve been very well supported here,” he said. “I’ve been able to do my work and not have to worry about the sharp elbows of academic politics.

“But scientists don’t work in isolation and the spotlight shouldn’t only be on me,” he added. “We’re a high-performing group and this work would not be possible without a key number of collaborators. They’re all critical to our success.”

To support Dr. Kendler’s work, make a gift online or contact Bernadette O’Shea, senior director of development, at (804) 828-3652 or bernadette.oshea@vcuhealth.org.